PICTURE-TAKING FINALLY ALLOWED. Government announced free admission for all government-run museums in celebration of the 112th anniversary of Philippine Independence. On that day we went museum hopping around Luneta and Intramuros. While we were able to save a few bucks to see the Spolarium at the National Arts Gallery, we were disappointed to pay the 75 pesos entrance fee in Fort Santiago which is managed by the Intramuros Administration, a government agency.

Nothing spectacular has been added to Fort Santiago since our visit in 2008 except for the function area built from the ruins of the old Spanish Storehouse which was off limits that day. Thankfully, the National Historical Institute who runs the Jose Rizal Shrine at Fort Santiago has permitted picture-taking inside the museum. Picture taking has been banned from most museums, but for a family who regularly visits national landmarks, this initiative by NHI makes our trips more engaging and memorable.

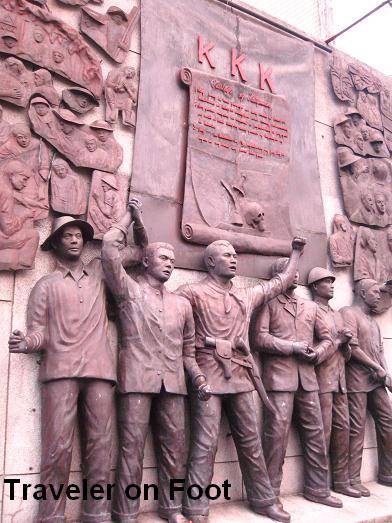

FORTRESS OF THE SPANISH EMPIRE. Fort Santiago in Intramuros was built in 1571 to protect the mouth of the Pasig River. It was a strategic Spanish military fortress that holds many Tales of Death from its Dungeons and Jail Cells.

During World War II, hundreds of the Filipinos and American soldiers imprisoned in its dungeons died from drowning while the waters from the Pasig River flooded the cells during high tide.

RIZAL’S JAIL CELL. One of the fort’s famous prisoner was Jose Rizal. The Filipino national hero was incarcerated in the fort until he was marched to The Killing Fields of Old Manila -Luneta. A national shrine was built in his honor from the ruins of a Spanish military barracks at Fort Santiago.

RIZAL SHRINE. We entered the Rizal Shrine using the entrance on the side of the reconstructed barracks. Quartered on the ground floor are quaint items ranging from the classic to the macabre museum pieces including some books, medical tools, photos, and pieces of sculpture displayed in vertical showcases.

MI ULTIMO ADIOS. Since its opening, taking pictures were not encouraged inside the museum until recently when NHI chairman and historian Ambeth Ocampo allowed visitors to take souvenir pictures inside the national landmarks.

Rizal’s prison cell was located in the old pantry. It is in this room where Rizal has supposedly written the Mi Ultimo Adios on the eve of his execution, which he hid in a food warmer given to him by the Pardo de Taveras. The food warmer and a reproduction of the original manuscript printed on a 9×15 centimeter paper are displayed in one of the rooms on the second floor.

The Mi Ultimo Adios is considered as one of the most moving and beautiful poems written in Spanish and was penned perfectly without erasures or drafts. Some historians believe that Rizal has planned every heroic detail of his life including his valedictory poem which he wanted everyone to believe he has written overnight.

Whether planned or not, the genius in Rizal is not diminished. Nick Joaquin suggested that the poem has been running through his head during his incarceration, and maybe even before that; and what he wrote down on the night of December 29, 1896 was but the final and complete version of a poem long in progress.

RIZAL’S VERTERBRA. Three years after Rizal’s execution, his family were allowed to exhume his remains from Paco Cemetery to their home in the San Nicholas District in Binondo. Later, all the bones were given rightful honors and were interned under the Rizal monument in Luneta except for a section of his vertebra.

Upon reaching the second floor, we entered a room where a piece of Rizal’s vertebra is displayed in a glass urn. Closer look at the piece of vertebra reveals a cracked or a chipped portion believed to be where the bullet from the firing squad hit Rizal on December 30, 1896.

RIZALIANA FURNITURE. Leaving the old Spanish barracks, we walked on top of the curtain wall connecting the old barracks to the Baluarte de Sta. Barbara which houses the Rizaliana Furniture Collection. The furniture and furnishings on exhibit were donated to the Philippine government by Trinidad Rizal, the unmarried sister of Jose Rizal to whom the food warmer containing the legendary valedictory poem was handed over.

In 1954, the descendants of Saturnina Rizal-Hildago, eldest sister of Jose, turned over various furniture from the Idyllic Ancestral Home of the Mercados in Calamba including the dining set, four-poster bed, and a number of aparadores.

Also on display are furniture pieces used by the Rizals during their exiled in Hongkong. The sofa, washbasin and stand were used by Rizal in his clinic in Hongkong.